|

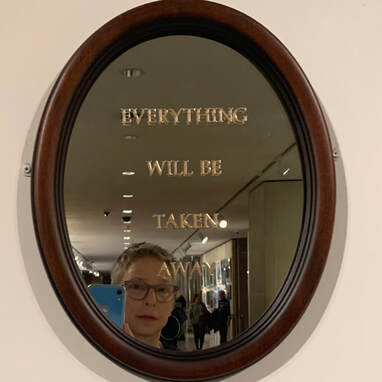

art: Adrian Piper For the last few years of my twelve-year relationship with Joe, one of his Word Paintings hung in my living room. It was a large, three-panel affair in vibrant yellow, green and blue that announced, “I wanted to reveal my secrets.”

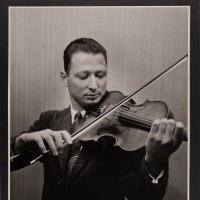

On the final day of our relationship, I stretched out in my lounge chair as the lights in the buildings around mine went on--the big city version of stars coming out. You can feel yourself settle in to the slower evening rhythms, aware of the universe from a quiet distance, but snug in your own world. The painting hung in my line of vision, but I gave it no thought. With Joe flying off to see family earlier in the day, I was enjoying the breath of solo time. A partnership can do that. Make that time alone a respite. Because every partnership needs it. And because you know that it’s temporary, a breeze that isn’t going to turn into a desolate gale. I opened my laptop. And Joe’s email was up on my screen. “Just close that window,” I thought. But I also thought about a recent hurtful lie, from this man I’d trusted to my bones. So, I went looking. Reveal his secrets those emails did. The recent ones at the top of his cue. The ones I had to scroll to, my index finger taking me years back. The gut punch when I put [redacted] in the search bar and up came the motherlode, scores of messages, my search term screaming at me over and over in yellow highlighter. As far back as the beginning of our relationship and before. His response to my discovery? “It’s nothing. Just a little titillation.” Then he ran. Out of sight, didn’t happen. For the next month, he made me invisible. My calls ricocheted straight to voicemail without a single ring. I heard the gentle amusement in his outgoing message, his familiar cadences. The voice of a man I’d chosen for his reliability, his honesty, his solidity. That man was gone. My normally blue texts showed green. Blocked. My phone was a locked door. “Dude,” I emailed him, though I don’t know if he was seeing my email, “[Redacted] is absolutely nothing to be ashamed of. And having [redacted] in 2024 is pretty common. You could have talked to me about it. You could have talked to me about anything. But erasing me is unacceptable.” I didn’t hear from him. The ghost of my father appeared at the foot of my bed. My father, whom I adored and who had fits of rage. Me, drawing myself into a ball in the corner of my childhood bedroom, cheek to the nubby, blue rug, while my father, disappointed in the world and me, hit and kicked. The next day, it hadn’t happened. He sang funny songs as he marched around the apartment, made me tomato soup and crispy, golden, grilled cheese, watched Star Trek with me, put on a tux, picked up his viola, and went out to make beautiful music with a world-class orchestra. I let it go. I loved him, I was a daddy’s girl. Joe’s meltdowns weren’t violent. But like my father’s they weren’t acknowledged either. We didn’t fight much, but when we did, he shut down and shut me out until he’d swept the problem under the rug. And now I’d seen into a place so secret, that the shut down seemed permanent. My demons sent out party invitations. Separation anxiety made my heart race; I couldn’t catch my breath. My enduring feelings of not being heard pulsed in my ears. The invisibility that stalks women as we grow old enraged me. My lifelong insomnia took over. I slept for only a few hours a night, on a cocktail of drugs. I woke up in darkness, my chest cavity aching, my stomach hollow. Life can be a bitch, even for those of us who know how incredibly fortunate we are. Several decades ago, when a dear friend across the pond was hurting badly, I bought myself a plane ticket and said to her, “Vamos a pintarnos los labios de rojo.” We’re going to paint our lips red and go out and drink wine and leave lipstick traces on the glass.” Now she reminded me of this, got on a plane, and came to visit. We went out and saw art every day. We took extended walks through Central Park, winter sun winking on the reservoir. We cooked together. I’m not going to say my heartbreak went away, but friends are it. Friends are everything. My gratitude runs deep. One day we set out for the Museum of Modern Art, with a quick stop at the clothing giant, Uniqlo. I’d bought some long johns for Joe and hadn’t gotten around to giving them to him. I didn’t have the receipt, and was anticipating arguing for a refund. The young woman behind the sales counter had kind eyes and a round face. “I bought these,” I told her, “for my beloved, who died.” And as I said it, I realized it was true. My beloved was gone. In Jewish tradition, the family sits shiva when a loved one has died, spending seven days receiving guests. At the end of each shiva day, we say Kaddish, the prayer for the dead. At least the observant families do. We had sat shiva for my father and it was more like an Irish wake, but without the booze and without the merriment. In our secular circles, people didn’t know to come briefly, and not leave us their dirty dishes. They stayed for hours, stuffed their faces, made more noise than I could take. This lasted an unbearable week. One distant acquaintance asked for a doggy bag for some of the leftovers. And I didn’t know more than the first few foreign words of Kaddish, anyway. But we do need rituals when a beloved dies. “I’m so sorry,” said the salesclerk. Store credit in hand, off we went to MoMA. John Giorno’s Dial-a-Poem is a re-creation of his 1970 exhibit. Six old, black rotary phones sit on six wooden desks with six chairs, arranged in a circle. You sit down, dial a random number, and hear a poet reading their work. In the circle, you’re united with strangers doing the same, all of you listening to different poems. I took a seat, dialed 23 for the day of my birth. Through the receiver, Giorno announced, “Allen Ginsberg.” And then came Ginsberg’s reedy voice reading a snippet of his famous poem “Kaddish,” written after his mother died. I listened to him chant a handful of syllables from the prayer for the dead, and for the first time in a month, I cried. Sometimes the universe tells you what you need. I would create my own mourning rituals for Joe. That’s a neat little ending. Except. Even as I was crying in the middle of MoMA, I was vaguely aware that the chanting didn’t exactly sound like ancient Hebrew. After my declaration in Uniqlo of Joe’s death, I wanted Ginsberg to be saying the mourner’s Kaddish. But it could have been… a Hindu wail? A Buddhist invocation? I spent a few days considering what form my grief rites might take. Made three folders on my computer desktop: Joe’s Betrayal--screenshots; Unsent Emails--I am currently up to unsent email #35, and Love From my Friends--stuffed with texts and emails, voicemails, photos and other demonstrations of the support I’ve had through these painful weeks. I started telling people the story about Uniqlo and “Kaddish” and it made me feel better. I was going forward. I was going to bury the guy who’d buried me. I dug up Ginsberg on YouTube reading his poem, a fever dream telling of his mother’s life and death and Ginsberg’s grieving. It’s loong and rich, a good, hard listen. But it’s entirely in English, except for a few borrowed syllables of the actual Kaddish that sounded nothing like what I’d heard him reciting on that rotary phone. What was it I’d listened to, that day? I made a cup of ginger tea with honey and dove down an electronic rabbit hole. Seek and ye shall find. Clip after clip of Ginsberg chanting Buddhist mantras over many years. Here he is in grainy black and white footage with a group of fifty or so young people on the shores of a windy Lake Michigan, before the 1968 Democratic National Convention. And… yes! This was it! The chant from the museum! Hari om namah shivaya, Hari om namah shivaya. Na is Sanskrit for earth. Ma, water, Shi, fire, va, air, ya, ether. The chant means bow down to Shiva master of the elements. But what, I wondered, with deep respect for a god of Hinduism, was the use of this chant to an old Jewish pinko poet like Ginsberg? Or to old Jewish pinko me? Shiva is the destroyer. And avenger. The angry God. Okay, I was totally feeling that. But he also represents the inner self that remains intact after everything ends. Hmmm. Maybe there was something to this. “Hari om, namah shivaya,” I sang to my quiet apartment. And in plains laid to waste there is regeneration, there’s new life. Bow down to your own true self. Maybe my work wasn’t to bury anyone. Joe and I had twelve years of our own earth, water, fire, air, ether. I added a folder to my computer desktop with no title. Inside I started to put the memories—the stories, the photos, the songs, the private jokes. Mine. To have and to hold. At a what would one day be a comfortable remove. At 66, my world was fresh and new. Bow down to your true self, Eve Becker.

9 Comments

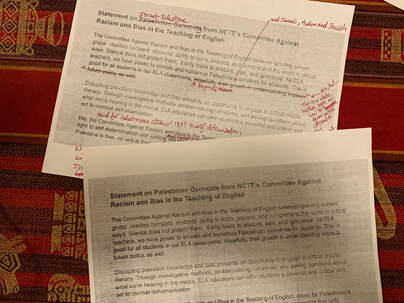

Dear members of NCTE's Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English,

After receiving the email from the NCTE Executive Committee distancing themselves from your statement, I of course went looking for the statement. And once I read it, I saw that though it took a partisan stance that NCTE Official couldn't sanction, it was a call to talk. Not to remain silent. So on my private blog, no official NCTE connection, I'm accepting the invitation. I agree 100% with the committee that ignoring the current situation is a deadly duck and cover. As English teachers, we encourage our students to step into each other’s shoes; we build bridges through reading and writing and talking. If we can’t discuss this with civility and compassion, who can? I’ve posted the committee’s statement in its original form, and then, by way of starting a respectful dialogue, edited it to remove triggers, acknowledge pluralism, honor multiple identities and keep people in the conversation, instead of shutting it down. The CaRBTE Statement: Statement on Palestinian Genocide from NCTE’s Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English The Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English believes ignoring current global realities hampers students’ ability to learn, process, and comprehend the world in critical ways. Silence does not protect them; it only leads to erasure, pain, and ignorance. As ELA teachers, we have power to elevate and humanize Palestinian narratives for students. This is good for all students in our ELA classrooms. Hopefully, their growth in understanding impacts future policy, as well. Disrupting prevalent knowledge and bias presents an opportunity to engage in critical media literacy. Through investigative methods, problematizing narratives, and asking questions about what we’re hearing in the media, ELA educators can offer students a powerful and critical skill set to combat dehumanization. We, the Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English, stand for Palestinian’s right to self-determination and justice. We stand against genocide. We recognize that until Palestine is free, no one is free. My edits: Statement on the Israel Hamas war from NCTE’s Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English The Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English believes ignoring current global realities hampers students’ ability to learn, process, and comprehend the world in critical ways. Silence does not protect them; it only leads to erasure, pain, and ignorance. As ELA teachers, we have power to elevate and humanize Palestinian and Israeli, Muslim and Jewish narratives for students. This is good for all students in our ELA classrooms and beyond. Disrupting prevalent knowledge and bias presents an opportunity to engage in critical media literacy. Through investigative methods, problematizing narratives, and asking questions about what we’re hearing in the media, ELA educators can offer students a powerful and critical skill set to combat dehumanization. We steadfastly resist Islamophobia and antisemitism. We challenge the conflation of Palestinians with Hamas, and Israelis and non-Israeli diaspora Jews with the Netanyahu government. These misconceptions breed bias and hate. We abhor the ongoing terror, the loss of life, home and family. No nation’s child is less important than another’s. We, the Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English, stand for the right of all human beings to have self-governance, safety and basic necessities. We call for an immediate cessation of the violence, for humanitarian aid, and international support for negotiating a sustainable, humane peace. We recognize that, in the words of Fannie Lou Hamer, nobody’s free until everybody’s free. Resources for teaching: [TK] Reading list for teachers: [ditto] Photo: Woman walking in front of Picasso's Guernica. From Euronews by Francisco Seco. October 21, 2023 [Confused, heartbroken, lonely. Raw first draft banged out upon awakening. I will never get this one right, nor will I get to listen to and learn from the people I’m connected to, if it sits on my computer.] I had a dream. Literally. Last night. A weird little nightmare of sorts. Or a maybe a gift, because it crystallized some of my thinking, my obsessive thinking, over the past two weeks. I’m protesting in front of the Capital building for an immediate ceasefire in Gaza. Around me are my fellow humanitarian Jews, and Muslims, allies, people who look like the beautiful mosaic we occasionally are, in this country. The police begin arresting us. Nearby, I see--packed in the crowd with me—an old student, an Arab-American Muslim woman I taught as an 8th grader at least twenty years ago, and who was one of my favorites. I manage to make my way to her and we embrace. We hold each other in warm reunion, and hang on, offering unspoken comfort as horror rips a faraway part of the world, with ripples for both of us.

While we’re hugging, two cops come close and fasten handcuffs and a leg cuff on us—grass green plastic affairs, and there’s only one set of cuffs for the two of us, so we’re united in our arrest. Don’t ask me how this works. It’s dream-magic, where one set of cuffs is enough. Sinophobia and antisemitism entwined in RFK's ridiculous, dangerous rant. Why am I not surprised?7/18/2023 image: Leah Ai Tian, heroine of Fair Square Comics' "The Last Jewish Daughter of Kaifeng" by Fabrice Sapolsky, with Fei Chen, Ho Seng Hui, Will Torres, Exequiel Roel and Walter Pereyra Let’s agree that RFK Jr. is not a well man and perhaps have a bit of compassion for the rich asshole with the tin foil hat and the big soapbox.

|

Eve's BlogI've been blogging since 2010. When I've got writer's block in every other way (frequent), this low stakes riffing to think has been a constant. Over the digital years, I've had a half dozen or so blogs including a travel blog and a reading blog, both on Blogger, and an all-purpose blog on tumblr where I wrote about education, social equity and anything else that sparked me. I also posted some of my published print work on my website. My shit is all over the internet. I'll be using this space for the occasional blog post, now. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed