|

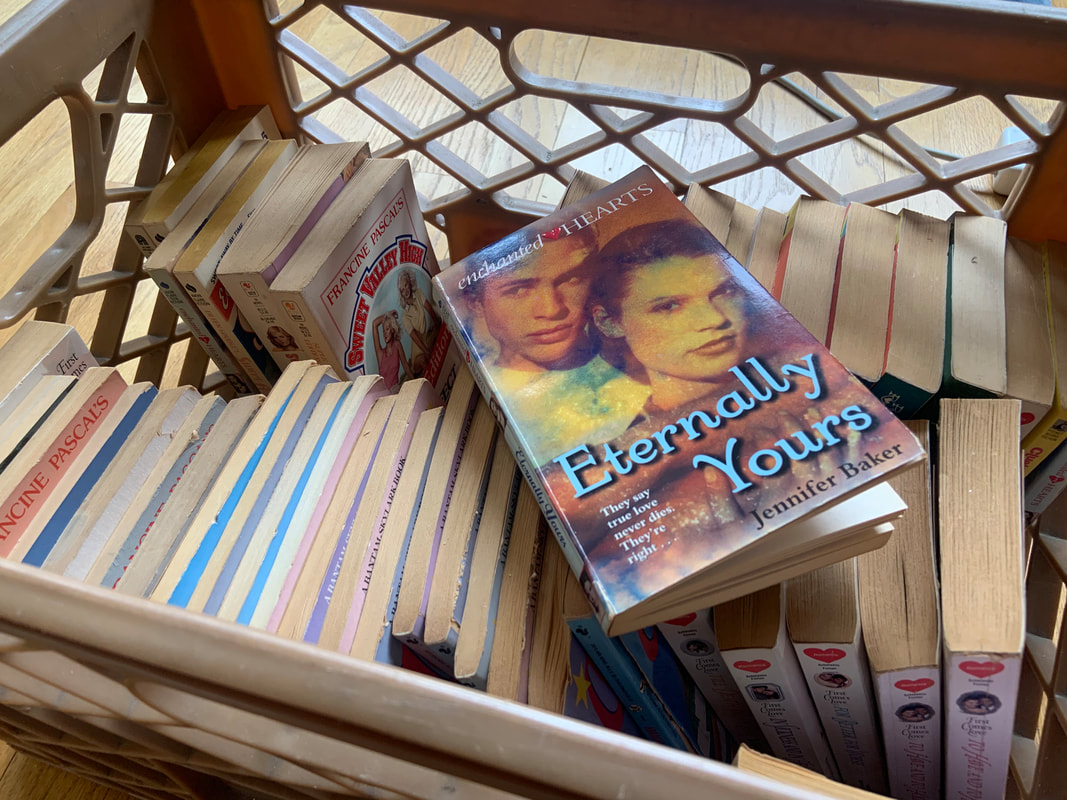

In my first career, I normalized whiteness in a generation of young readers. [A version of this piece was published by Chalkbeat, where they had me tighten it (a plus for the structure, a definite minus for the voice), and insisted that I "land" somewhere, making me take the questions out of the ending. I'm truly grateful to them for the ink, but deleting the interrogative mode? Really? I mean, teachers are supposed to open up discussions.] I grew up talking about race and class and equity at my dinner table, with my first gen activist parents. I taught a culturally sustaining curriculum to a diverse student body for two decades. But in my first career, I normalized whiteness for a generation of young readers. I am a retired middle school English teacher. White. Jewish. I leave a legacy of beautiful students whom I’ve been honored to teach. But once upon a time, as it were, I wrote books for young readers. All through the 80s and 90s, I pumped out YA and middle grade genre fiction. I started out editing teen romances. I went on to write my own--series books produced under tight deadlines where I sometimes had to smack out the whole thing in two weeks.I was a factory. I sat down at my IBM Selectric typewriter and wrote 35,000 words and didn’t look back. Didn’t reread. Didn’t edit. (To my former students, close your ears, my darlings.) I sometimes told people I was a typist. I taught myself to write later, when I was a teacher, digging into literature with my students. It’s a great way to learn to write. I didn’t find my true voice until I stopped writing to pay the rent. But my commercial books sold. A few were bestsellers. Maybe I told a decent story. I certainly undervalued what I took away from those years: The ability to write on spec. To a word count. To keep a plot moving. To get a character down in a few pen strokes. (Honey, I mean this literally. I wrote my first YA novel on a yellow legal pad.) When you think about most writing for skool--the deadlines, the targeted goals, the pressure to deliver a certain kind of anticipated product, perhaps my first career prepared me well. (And perhaps we should be teaching writing differently. But that’s for another rant.) Those were the days when series fiction for young adults was becoming big business. An industry. With its own section in the bookstores. And I worked for the titans--marketing visionaries who knew how to deliver a frothy, irresistible confection. Recently, I’ve been thinking about the normalized whiteness in all those kids books from the last couple of decades of the twentieth century. (Ah… she finally got to the thesis. After a whole page. Well, former students, there are all kinds of ways to write. Don’t let anyone tell you differently.) When I was a young editor, just starting out, I remember discussing the lack of diversity in these books with a boss. Where were the Black kids? “They don’t read,” my boss told me. “There’s no market for that.” Sit with that. I’ll put a couple of line breaks in here. Eventually, my boss did put a Black model on the cover of one of our signature romance lines. And hired... a white writer to write the Black protagonist. (Left out entirely--as it usually was at the time--was any discussion of kids who were brown, Asian, or anything besides Black or white. But the binary discussion of race in those days is another topic.) It fell to me, a white editor, to edit the book. I proceeded to remove certain tropes so astonishingly racist that I just sat at my desk shaking my head. She didn’t mean to offend, the author. She did her best to write an appealing, authentic heroine. But she’d drunk these tropes with her baby formula. I think I called my then-husband, and read him some of the parts I removed. But I didn’t discuss this with anyone else. I was part of the factory. And what about my books? I was a red diaper baby, whose grandparents came to this country looking for a refuge from hate, and whose parents were willing to fight for their ideals. But I also spent the first forty years of my life--until I became an educator--in a world that was mostly white. With whiteness as the default. My publishing colleagues and editors, for example, were white. Every single one of them. It has taken me years of reading, discussion and reflection to understand that my critical conscience growing up involved a vein of othering: Yeah, I see color; and it requires an extra step to shed some knee-jerk preconceptions. Moreover, my white, progressive sense of exceptionalism remains with me; there’s always more to understand and uncover. Back to those books from the 80s and 90s. I usually keep my career writing kids fiction in a deeply recessed mental file. Out of sight, out of mind. I never felt comfortable owning those hastily cracked out, commercial reads that were my bread and butter. That part of my life is long over, and my identity as an educator is strong. Let those sleeping dogs yellow and fade. But a social media post from a long-ago colleague, and a letter from a middle-aged fan who’d tracked me down, got me thinking about that part of my life, again. I took the box of books I'd written down from the high shelf where they'd been sitting, untouched, for decades. Thirty-something teen and middle grade novels, written under nine different names and pseudonyms. I began with one that a reviewer had singled out for its “diverse supporting cast and authentic dialogue.” Maybe it wouldn’t be as bad as I’d feared. But it was. Okay, yeah. I had some “diverse” secondary characters. Like... the occasional “pretty black girl” (not capitalized in the late twentieth century), the “dark-skinned dreamboat” with the obvious Latinx name, the “Korean” roommate--100% American, with immigrant parents. Please kill me. Most of my books' characters and all the protagonists were white. By default. There wasn’t--surprise, surprise--a single time that I described any of my white characters by race. Less obvious, but perhaps equally problematic, were the characters who were BIPOC in name, only. I kept myself amused, during my writer-for-hire years, by naming my characters, in a slightly modulated fashion, after people I knew. So upon rereading, I could tell that the girl on page 26 of Book Three of the series I wrote in 1988 is Black, because I borrowed her name from two of my Black elementary school classmates. But there is no way a reader could tell this. White as far as the eye could see. Gender norms? Don’t start me. And can we talk about how I erased my own identity from these books? Not a single protagonist is Jewish. They’ve got last names like Miller and Powell. And I’ll be gosh-darned if one of them doesn’t have a father who is a reverend. Um, really? Those Miller and Powell girls came from the suburbs, of course. From a land of tan and white stations wagons, football games and proms, none of which were personally familiar to this native New Yorker. The Miller and Powell kids had two-parent families, sat down to dinner together, were able-bodied and aggressively heteronormative. That was the market. Or so it was said. (I drank a half bottle of rioja as I dipped into that box of books, and talked aloud to myself as I read. But on a bright note, if you think we haven’t made any progress in the last decade or two, check out some of your old books. You’ll see we are making strides.) In sixth grade, I was exiled to the school hallway because I refused to stand up for the Pledge of Allegiance, my protest against U.S. involvement in Southeast Asia. I thought of myself as a rebel. As an advocate for change. But my books normalized a white, suburban shibboleth that was synonymous with series fiction for young readers. And this, Matilda, is what anyone of any race or group in this country over the age of twenty-five or so, grew up with. Default whiteness. In our books. Our movies. Our TV shows. Christian hegemony. Genderization. Every other identity erased. Yes, I also found two book proposals dear to my heart that featured characters from different backgrounds, and that I hadn't sold. They were relegated to my dead letter file. An old professional bio that describes my shifting professional life, from commercial fiction writer to content creator in the brand new world of digital media to--finally--educator, describes teaching as “the most deeply meaningful and fulfilling experience of my career.” No doubt a big part of that was working at a job that aligned better with my image of myself, a job that allowed me to tend to my students’ identities while tending to my own. But what to do about that box of books? For me, there’s only one option. Put them back up in the closet. Young readers finally have all sorts of choices that paint a richer, more authentic picture of who we are, and who we want to be. We white, lifelong progressives of a certain age like to think we weren’t part of the problem. Because of what I once did for a living, I have a written record that I was. But there’s a larger question at stake. Let's move from series fiction to major league literature. What do we do with all those substantial works from our past that also normalize whiteness--and that baptized us (listen to the Jewish gal--it’s built into our language, folks) as readers and thinkers, the ones teachers taught because the sentences sing, the ones that are our common hearth, our classics, our canon? (Yes, my lovely former students. I have moved on to another topic. You thought my teen romances were the subject, but they were actually the set-up. That story structure chart? The graphic organizers? The checklists? Useful only to a point.) After inventorying my books, I did another inventory of my curriculum for the last twenty years. Whew. A good list of reads for my oh so varied students. Beautiful books by authors of so many backgrounds. (I corked the rest of the rioja.) And there was my classroom lending library--a labor of love and obsession of which I was always annoyingly proud and was full of windows and mirrors, book choices where any member of my class could find a reflection of themselves, or an opening into someone else’s world. This didn’t negate the box of teen fiction, but could I forgive myself, just a little? I’d learned. I’d gotten better. The students I’d taught had read diverse works of literature. They’d also read classics. To Kill a Mockingbird for example, which I taught for a number years in the early 2010s. With its white protagonists, its white savior of a hero, and its Black characters that need saving, many teachers have now axed it from the syllabus. In the years before educators began discussing the book’s issues at conferences and in online forums, I asked my students to delve into the ways that Harper Lee was a product of her time; I invited them to examine the book’s communities--and author--with a reflective eye. A social map of Maycomb was one assignment. TKAM was on my syllabus--paired intentionally with Richard Wright’s Black Boy--because it’s a gorgeous piece of literature, unusual in structure, magnificent in language, with complex young characters and an important message about stepping into each other’s shoes. And isn’t it worth considering why it was radical in its time, became a perennial, but now shows its racial fault lines? Isn’t that part of examining history, examining ourselves, and understanding where we have come from and where we need to go? I leave these questions open for discussion. If I were still in the classroom, would I keep the classics on my syllabus? Which ones? Ones that contain offensive tropes? That eliminate BIPOCS? What about the ones that "just" normalize whiteness? I do believe that those who don’t analyze history are doomed to repeat it. During my final years in the classroom, I said, let's read the classics with intention. As beautifully crafted pieces of literature and primary sources of white supremacy. Flowers and thorns. Along with a freshly blooming canon. And ask who’s on the pages. Who’s not. Whose eyes we’re looking through. Parse the context. But that box of teen romances made me confront how deeply entrenched the subliminal message in those books—my books--was. With their unconscious erasure. Their twisted history. Their systemic racism. And those were books that had “a diverse supporting cast.” How many generations will it take to banish those messages? Can we vanquish them while still reading them, watching them, metabolizing them? My own books made me consider, for a moment, the notion of a curriculum without any of the old canon at all. (Frankly, I think The Scarlet Letter has a compelling plot, but that it’s a terribly written book. After rereading it as an adult, I’m happy never to read it again.) I’m fighting with myself, right now, about the role of our Old Faithfuls in our classrooms. What do we read in school and how do we read it? How do we not just expand the canon, but refocus it? How do we go from where we are to where we need to be? Fellow teachers, inquiring minds want to know. Former students, it would be especially meaningful for me if you would weigh in. I want to open up the discussion, here. [Thx for reading. The 'like' button here on Weebly sites is only an anonymous counter, and doesn't let me know who has 'liked' this post. So pls. leave me a word in the comments, or 'like' on FB instead.]

7 Comments

|

Eve's BlogI've been blogging since 2010. When I've got writer's block in every other way (frequent), this low stakes riffing to think has been a constant. Over the digital years, I've had a half dozen or so blogs including a travel blog and a reading blog, both on Blogger, and an all-purpose blog on tumblr where I wrote about education, social equity and anything else that sparked me. I also posted some of my published print work on my website. My shit is all over the internet. I'll be using this space for the occasional blog post, now. Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed